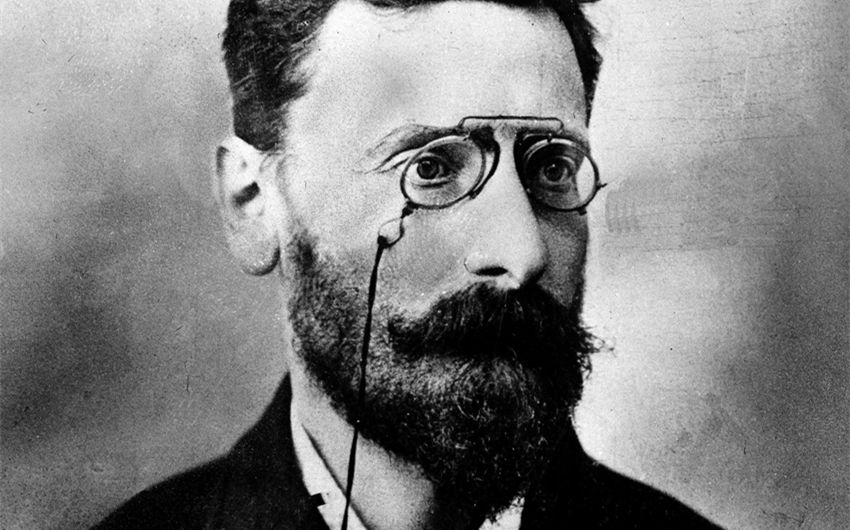

Joseph Pulitzer is one of those names you’ve heard a hundred times without fully meeting the person behind it. Yes, he’s the Pulitzer Prize Pulitzer—but he was also a relentless newspaper builder, a political reformer, and a complicated figure who helped invent the modern media playbook. If you want the real story, you need to look past the award and into the messy, high-stakes world he worked in: big-city corruption, industrial wealth, mass immigration, and newspapers competing like prizefighters for attention.

Who was Joseph Pulitzer?

Joseph Pulitzer (1847–1911) was a Hungarian-born immigrant who became one of America’s most influential newspaper publishers. He rose from poverty to power by mastering what the public wanted from news: clarity, urgency, and stories that felt connected to everyday life. He’s best remembered for building major papers like the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the New York World, and for endowing the Pulitzer Prize—one of the most prestigious honors in journalism, literature, and music.

But Pulitzer’s legacy isn’t just “good journalism.” It’s also the birth of mass-market news culture: banner headlines, aggressive investigations, crusades against corruption, and sometimes sensationalism used as a weapon to win readers.

Early life in Europe and why he left

Pulitzer was born in Makó, in the Kingdom of Hungary, into a Jewish family. His youth unfolded in a Europe full of political upheaval, rising nationalism, and limited opportunity for many young men without wealth or connections. He was ambitious, restless, and looking for a way out—especially after family finances worsened.

When you read about Pulitzer’s early years, one detail keeps repeating: he wanted a bigger stage. The United States, with its promise of reinvention, offered exactly that. He didn’t arrive as a polished intellectual hero. He arrived as a teenager with a sharp mind, a stubborn will, and the kind of hunger that makes you either break or build.

Arriving in America and fighting in the Civil War

Pulitzer came to the United States in 1864, during the final year of the Civil War. Like many immigrants who landed with little money, he found a quick path to stability through military service. He enlisted in the Union Army, which gave him pay, food, and a foothold in his new country.

This period matters because it shaped how he understood America: not as an abstract ideal, but as a brutal, competitive place where status had to be earned. After the war, he bounced through odd jobs and struggled with English, but he also absorbed the rhythm of American public life—politics, power, and the role newspapers played in shaping what people believed.

St. Louis: the launchpad for his newspaper empire

Pulitzer’s rise began in St. Louis, a city bursting with post-war growth, immigrant communities, and political deal-making. He learned English fast, read obsessively, and took a keen interest in politics. He also discovered something that changed his life: newspapers weren’t just businesses. They were power.

He started as a reporter and quickly moved into ownership. In 1878, he merged two struggling papers into the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. This wasn’t a gentle upgrade—it was a transformation. Pulitzer pushed a style that mixed aggressive reporting with a moral mission: expose corruption, fight monopolies, defend ordinary people, and make the paper impossible to ignore.

If you’ve ever wondered how newspapers became engines of reform, this is a big part of the answer. Pulitzer believed you could sell papers by serving the public interest—but also by telling stories in a vivid, dramatic way that made people feel something.

Buying the New York World and entering the national arena

In 1883, Pulitzer purchased the New York World, a struggling newspaper in the most competitive media market in the country. New York was not St. Louis. It was louder, richer, more ruthless, and filled with rival publishers who treated circulation like a blood sport.

Pulitzer turned the World into a powerhouse by doing three things exceptionally well:

He made news feel personal. Instead of writing only for elites, he wrote for working people—immigrants, laborers, shopkeepers—anyone who felt ignored by polished society papers.

He invested in investigations. He funded reporting that exposed city corruption, unsafe conditions, fraud, and political scandals.

He perfected presentation. Pulitzer embraced big headlines, illustrations, human-interest stories, and a fast, accessible writing style. It wasn’t “dumbing down” so much as “opening up.” He wanted the paper to be readable, emotionally gripping, and impossible to put down.

That combination built massive circulation and changed how American media operated. The newspaper became a daily habit for millions—less like a bulletin and more like a living public conversation.

The “yellow journalism” era and the Hearst rivalry

You can’t talk about Joseph Pulitzer without facing the most controversial chapter: the rivalry with William Randolph Hearst. Their competition pushed newspapers toward louder, more sensational coverage—especially in the 1890s.

This period is often summarized with the phrase “yellow journalism,” meaning a style that favored dramatic headlines, emotional storytelling, and sometimes exaggerated or thinly sourced claims. The term is tied to a popular comic strip character (“The Yellow Kid”) associated with the era’s fierce circulation wars.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Pulitzer helped create the incentives that made sensationalism profitable. He didn’t invent exaggeration, but he did prove that attention could be manufactured at scale. And when you’re fighting a rival like Hearst, the temptation to go bigger, faster, louder becomes constant.

That said, Pulitzer’s story is not a simple “villain of sensational news.” He also funded serious investigative reporting and supported reform campaigns. He lived in tension: public service on one side, business pressure on the other. And that tension is still the core struggle of media today.

The Spanish-American War debate

Many people associate the yellow journalism era with the lead-up to the Spanish-American War in 1898. Newspapers, including Pulitzer’s and Hearst’s, published dramatic stories about events in Cuba and about Spain’s actions. Critics argue that sensational coverage helped inflame public opinion and contributed to war fever.

Historians debate how direct that influence was, but as a reader today, you can take away something practical: Pulitzer’s era showed how media can amplify emotion faster than facts can stabilize it. It’s a lesson that still matters whenever headlines outpace verification.

Political power, reform campaigns, and the publisher as crusader

Pulitzer wasn’t just running a paper. He was shaping politics. He believed newspapers should act as watchdogs—going after bribery, machine politics, and corporate abuse. The World often positioned itself as a champion of the “common person,” which made it both popular and dangerous to powerful interests.

But Pulitzer’s politics weren’t always neat or predictable. He supported reform, yet he also understood how to use influence. He attacked corruption, yet he sometimes played the political game aggressively. If you’re looking for a clean hero narrative, you won’t find it here. What you find instead is the birth of modern media power: a publisher who could sway elections, expose scandals, and pressure institutions.

A landmark moment: the Statue of Liberty pedestal campaign

One of Pulitzer’s most admired achievements was helping fund the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. When wealthy donors and politicians failed to raise enough money, Pulitzer used the World to launch a public fundraising campaign. He encouraged ordinary people to donate small amounts and printed contributors’ names in the paper.

This wasn’t just charity. It was a masterclass in civic mobilization through media. He proved that a newspaper could rally a nation—not by begging billionaires, but by making the public feel ownership of a national symbol.

Health struggles, near-blindness, and retreat from daily operations

As Pulitzer aged, he suffered serious health problems, including worsening eyesight and chronic illness. He became increasingly isolated and spent long periods away from the newsroom. Even so, he remained deeply involved in editorial direction, often communicating through intermediaries and correspondence.

This part of his story is oddly modern too: the powerful leader who can’t fully be present physically, yet still shapes decisions from a distance. It also adds a layer of tragedy. Pulitzer’s hunger built an empire, but it also consumed him. The job never really stopped.

The Pulitzer Prize and why he created it

Pulitzer’s most enduring legacy is the Pulitzer Prize, established through his will. He also provided funding for a journalism school at Columbia University, with the idea that journalism should be trained, studied, and improved—not left entirely to instinct and competition.

There’s a certain poetic irony here. Pulitzer helped drive the era of louder, mass-market journalism—and then he used his fortune to encourage higher standards and public-minded reporting. It’s not that he “repented.” It’s that he understood the stakes. He knew media could be a force for reform or manipulation, and he wanted to push it toward the former.

The Pulitzer Prizes today cover journalism, letters, drama, and music, reflecting Pulitzer’s belief that public life isn’t only politics—it’s also culture, storytelling, and the shared narratives that shape a society.

What Joseph Pulitzer got right, and what still feels uncomfortable

If you want to judge Pulitzer fairly, you have to hold two truths at the same time.

He professionalized public accountability. He funded investigative reporting and normalized the idea that newspapers should challenge power, not flatter it.

He mastered mass persuasion. He helped make attention a currency, and that created incentives for sensationalism—sometimes at the cost of nuance.

When you look at today’s media landscape—clickbait headlines, outrage cycles, investigative nonprofits, major exposés, and public campaigns—you’re seeing Pulitzer’s fingerprints everywhere. He didn’t create every tool, but he helped prove which tools worked.

Featured Image Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Pulitzer