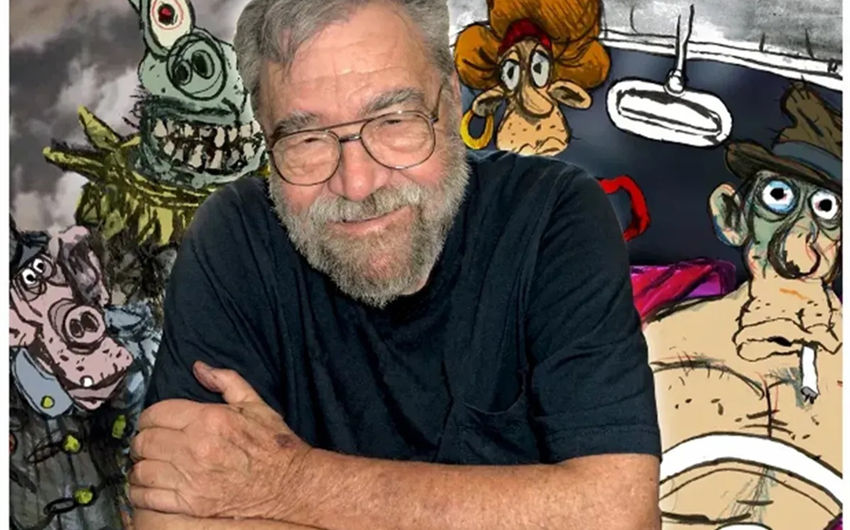

Ralph Bakshi is the reason “adult animation” became a serious phrase instead of a punchline. Long before streaming platforms treated animated shows like prestige TV, Bakshi was already pushing animation into territory studios didn’t want to touch—sex, racism, street life, war, desperation, and the strange poetry of big-city survival. If you’ve ever wondered how animation escaped the kids-only box, you’re really asking about Bakshi: the filmmaker who proved cartoons could be raw, political, ugly, funny, and undeniably human.

Who is Ralph Bakshi?

Ralph Bakshi (born October 29, 1938) is an American animator, director, and artist best known for turning animation into a vehicle for adult stories in the 1970s and beyond. He’s not “the guy who made one controversial movie.” He’s the guy who built an entire alternative lane—independent, provocative, and unapologetically different from the polished studio style most audiences thought animation had to be.

Bakshi’s signature is a mix of street-level realism and surreal imagination. One minute you’re in a grimy neighborhood filled with hustlers and broken dreams; the next you’re in a fantasy world that still feels bruised and political. He makes you feel the texture of a place—the noise, the heat, the ugliness—then he turns that texture into animated motion.

His early life: from Haifa to Brooklyn grit

Bakshi was born in Haifa and moved to the United States as a child, growing up in Brooklyn. That Brooklyn upbringing mattered. You can feel it in his work: the crowded streets, the sharp humor, the constant tension between hope and hardship. Even his fantasy stories often carry a city kid’s instincts—mistrust authority, watch the angles, don’t romanticize violence, and never pretend life is clean.

Before he became “Ralph Bakshi,” the boundary-breaker, he was just a kid obsessed with drawing and comics, absorbing the world around him and turning it into images. That foundation—visual storytelling first, everything else second—never left him.

Starting in TV animation and learning the rules before breaking them

Bakshi worked in traditional animation environments early on, including studio work that trained him in the mechanics of production: deadlines, assembly-line processes, and the reality that animation is both art and labor. He learned the rules the industry lived by—then spent the rest of his career testing how far those rules could bend before they snapped.

That background is important because his later films weren’t “accidents.” They were deliberate rebellions made by someone who understood how the system worked. He knew exactly what mainstream animation looked like—and exactly why he didn’t want to make it.

Fritz the Cat: the film that blew the door open

Fritz the Cat (1972) is the title that turned Bakshi into a headline. It’s often described as the first X-rated animated feature released by a major distributor in the United States, and it shocked audiences who couldn’t process the idea that a cartoon could be explicitly sexual, profane, and politically charged.

If you only look at the controversy, you miss the real impact. Fritz proved there was a paying audience for animation that didn’t cater to children. That single proof changed what was possible. It didn’t instantly create an industry of adult animated films, but it cracked the assumption that animation was automatically “safe” and “family.”

Bakshi became a symbol—sometimes celebrated, sometimes attacked—but either way, the conversation had shifted. Animation could be dangerous now. And he liked it that way.

Heavy Traffic: when Bakshi made the city the main character

Heavy Traffic (1973) is where you start to see Bakshi’s deeper obsession: urban life as a complicated, violent, funny, heartbreaking ecosystem. The film blends rough sketch-like animation with live-action elements and a kind of streetwise improvisational energy. It doesn’t feel like a neat “story” as much as a feverish memory of what it’s like to grow up surrounded by temptation, poverty, and chaos.

This is the point where Bakshi stops being just “the guy who made the dirty cartoon” and becomes something more interesting: a filmmaker using animation as adult literature—messy, uncomfortable, and emotionally specific.

Coonskin: controversy, satire, and why it still divides people

Coonskin (1975) is one of Bakshi’s most controversial films, and it’s also one of the clearest examples of his risky instincts. The movie attacks racist imagery and stereotypes by exaggerating them into grotesque satire—an approach that some viewers see as exposing racism, and others see as repeating harmful visuals, even if the intent is critical.

The reason it still divides people is that satire is a dangerous tool. If your audience doesn’t read the critique, they may only see the stereotype. Bakshi often operated in that danger zone: he wanted the audience to feel uncomfortable enough to think, but discomfort can also turn into backlash. Whether you view Coonskin as brave or misguided, it shows you what Bakshi was trying to do: use animation as social confrontation, not entertainment comfort food.

Wizards: fantasy with a bruised political spine

Wizards (1977) is Bakshi’s pivot into fantasy, but it’s not the kind of fantasy that exists to soothe you. It’s an anti-war story wrapped in weird creatures, magic, and a world scarred by ideology. The film is also notable for how Bakshi blends animation with real-world imagery, creating a jarring reminder that fantasy violence still echoes real violence.

This is where you start to understand Bakshi’s true range. He isn’t trapped in “urban grit.” He’s using whatever genre gives him leverage to talk about power, propaganda, and the seduction of authoritarian thinking. Even when the film gets playful, the worldview stays sharp.

The Lord of the Rings: rotoscoping ambition and a divided legacy

Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings (1978) is one of the most talked-about adaptations of Tolkien’s work, partly because it was so ambitious. He used extensive rotoscoping—filming live-action performances and animating over them—to create movement that felt heavier and more realistic than standard animation.

For some fans, that rotoscoped style is exactly why the film works: it makes Middle-earth feel physical, muddy, lived-in, and dangerous. For others, it’s distracting or uneven. Either way, it’s a Bakshi move: take a beloved property and refuse to make it soft. His version of Tolkien doesn’t feel like bedtime myth. It feels like war told by someone who believes war is ugly.

The film also has a “what could have been” aura because it covers only part of the story. But even in that incomplete form, it left a mark. You can trace its influence in later fantasy filmmaking and in how animation gets used to depict epic scale without losing human weight.

American Pop and Fire and Ice: two sides of his craft

American Pop (1981) shows Bakshi at his most emotionally expansive. It’s a sweeping story tied to American music and generational struggle—ambitious, heartfelt, and often more tender than people expect from him. If you think Bakshi is only about shock, this film corrects you. It’s still intense, but it’s also full of longing: the desire to create, to belong, to survive, and to turn pain into art.

Fire and Ice (1983), on the other hand, is Bakshi leaning hard into visual spectacle and fantasy pulp, created in collaboration with legendary fantasy artist Frank Frazetta. It’s all muscular movement, stylized bodies, and primal momentum. You watch it less for plot complexity and more for the visceral energy of the imagery—like a moving painting from the back of a 1970s fantasy paperback.

Cool World and later projects: uneven reception, continued experimentation

Cool World (1992) is often remembered as a messy, fascinating project—part live-action, part animation, loaded with style, and criticized for storytelling choices. But even when the results didn’t land cleanly, Bakshi’s impulse remained consistent: try something that mainstream studios wouldn’t dare to make on their own.

Later, he also worked in television, including projects like Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures and the adult animated anthology series Spicy City. That TV work matters because it shows Bakshi wasn’t just a feature-film provocateur. He was a builder of animation culture—someone who kept pushing different formats, different audiences, and different tones.

What Ralph Bakshi’s legacy really is

Bakshi’s legacy isn’t that he made cartoons “edgy.” It’s that he treated animation like a full-strength medium, capable of handling the same emotional and political weight as live-action film. He proved that animation could be:

Realistic without being tame. Stylized without being childish. Socially confrontational without needing a lecture. Beautiful without being polite.

You can also see his influence in how modern creators think about adult animation. Even when their tone is comedic, the permission structure Bakshi helped create is still there: you can animate for adults and not apologize for it.

Featured Image Source: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Creator/RalphBakshi